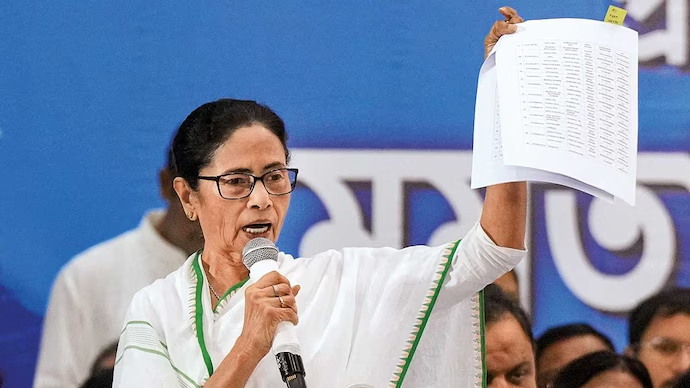

Kolkata: West Bengal’s political landscape has once again turned into a battleground between the Centre and the state government. Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has openly declared that she will not allow the implementation of the SIR—Samagra Nagarik Register (Comprehensive Citizen Register)—in the state. She has accused the Centre of attempting to interfere with citizens’ rights and privacy. But key questions arise: Does the Constitution give her the authority to block such a move? And why is Mamata Banerjee so strongly opposed to the SIR?

According to the Constitution, subjects related to citizenship, census, and national identification fall under the Union List. This means that only the central government has the authority to formulate policies on these matters. A state government cannot legally block or create policies in this domain. Therefore, if the Centre decides to implement the SIR, the state can register its protest but cannot legally prevent its execution. However, administratively, states can certainly slow down the process by withholding cooperation—much like what was seen earlier during the NPR and NRC exercises when several states declined to provide data support.

Mamata Banerjee’s opposition is rooted not only in constitutional interpretation but also in political and social dynamics. In several border districts—North and South 24 Parganas, Malda, Murshidabad, and Cooch Behar—there is a substantial population of refugees and undocumented migrants from Bangladesh. Their citizenship status has long been a sensitive political topic in Bengal. This section of the population significantly influences the vote bank of the Trinamool Congress (TMC). If SIR is implemented with strict verification norms, many individuals may find their citizenship under scrutiny. Thus, Mamata Banerjee has labelled the initiative as an attempt to “frighten people,” positioning herself as their protector.

NRC, NPR, and related exercises have previously triggered nationwide controversy. The Centre argues that the SIR is merely an official record of citizen data, aimed at improving the delivery of welfare schemes and reducing identity fraud. Critics, however, fear that the registry may disproportionately target Muslims and border populations. In Bengal—sharing a long international border with Bangladesh—the issue of illegal immigration has always been politically charged, making the state particularly sensitive to such measures.

Another crucial factor behind Mamata Banerjee’s resistance is her long-standing political rivalry with the BJP. The saffron party has consistently emphasized NRC and CAA to mobilize Hindu refugee groups, particularly the Matua community. In contrast, Mamata has projected herself as the “guardian of people’s rights” and has repeatedly assured residents that “no one will need to prove their citizenship as long as I am here.” While this claim lacks constitutional backing, it has become a powerful political message among her support base.

If implemented, the SIR would rely heavily on state machinery—local officials running enumeration, verification, and data collection. Lack of state cooperation could slow down the process significantly. However, the Centre can choose to deploy its own administrative setup if necessary. This is precisely where political confrontation meets constitutional limitations. Even with Mamata Banerjee’s resistance, completely keeping Bengal out of a nationwide registry exercise may prove difficult.

The larger question remains: Can the SIR truly act as a warning bell for illegal migrants? Theoretically, yes. If documentation is made mandatory, individuals lacking official records would face scrutiny. Bengal has a considerable population that, due to poverty, displacement, or migration, does not possess proper identification papers. These include not just undocumented migrants, but also Indian citizens who have historically struggled with documentation. This creates a risk that innocent civilians may get caught in bureaucratic crossfire—an argument Mamata Banerjee is exploiting politically.

In conclusion, Mamata Banerjee’s resistance is not merely against a proposed administrative exercise. It is a powerful political statement aimed at preserving her support base and positioning herself against the BJP’s larger citizenship narrative. While constitutionally she cannot block the Centre’s move, her symbolic opposition carries significant political weight. In a state where identity, migration, and history are deeply entwined, the SIR debate has transformed into a battle of political survival for Mamata Banerjee and a major flashpoint in Centre–state relations.