New York: He lived more lives than the characters he created. Before he became the master of the modern thriller, Frederick Forsyth had already been a fighter pilot, war correspondent, undercover informant, political insider, and survivor of gunfire. He didn’t just write about danger—he chased it, inhaled it, and turned it into storytelling fuel. While other writers imagined conspiracy, Forsyth uncovered it. While others plotted fictional coups, he witnessed real ones. And when governments tried to silence wars, he exposed them to the world.

At 32, he sat broke in a small English flat with nothing but a typewriter and memories soaked in conflict. One year later, he detonated onto the literary scene with The Day of the Jackal, a novel so meticulous and chilling that intelligence agencies reportedly studied it. It didn’t just sell millions—it redefined the thriller genre forever.

Yet behind the global fame was a man who never stopped moving through the shadows. From Nazi hunters to mercenaries, spies to presidents, Forsyth navigated the underworld of politics and power with fearless precision. Even in death, his stories refuse to rest—rising once again to confront the darkness he spent a lifetime unveiling.

This is not just the story of a writer.

This is the story of a man who lived his fiction.

Early Life: Seeds of Adventure

Frederick McCarthy Forsyth was born on August 25, 1938, in Ashford, Kent, England, into a home where books were treasured. His mother, a passionate reader, sparked in him a lifelong love for stories. Growing up during World War II, young Forsyth was mesmerized by the drama unfolding in the skies above England. The roar of fighter planes, tales of aces, and whispered stories of espionage planted the seeds of thrill, daring, and danger.

At the prestigious Tonbridge School, he excelled in modern languages. French, German, Spanish—he devoured them, unknowingly equipping himself for a career that would take him across continents and into diplomatic corridors. A brief stint at Granada University in Spain followed, but the classroom could not contain his curiosity. Forsyth wanted action, not theory.

Military Service: Wings of Youth

In 1956, at just 18, Forsyth joined the Royal Air Force (RAF)—becoming one of its youngest fighter pilots. He trained on the de Havilland Vampire, one of Britain’s earliest jet fighters, a symbol of post-war innovation and speed.

Flying taught him precision. Discipline. Fearlessness. He served in the RAF and later the Royal Auxiliary Air Force until 1958. These years in the cockpit didn’t just thrill him—they shaped his writing DNA. Every future novel would carry the pulse of risk he once felt in the sky. He later survived a real gunshot wound during freelance reporting—proof that danger followed him even after the RAF.

Journalism: From Desks to Danger Zones

By 1961, Forsyth shifted from flying to writing, joining Reuters and then rising to BBC assistant diplomatic correspondent in 1965. He covered the French-Algerian conflict, assassination attempts on Charles de Gaulle, and the Cold War power plays in Europe. His language skills opened doors—and borders.

But everything changed in Biafra (Nigerian Civil War, 1967–1970).

Sent to cover the conflict, he witnessed famine, massacres, and political manipulation. The BBC tried to censor the extent of the crisis. Forsyth refused. In an act of defiance, he resigned and returned as a freelance reporter—embedding himself in a war zone for nearly two years.

Out of this came The Biafra Story (1969) and Emeka (1982)—raw, unflinching accounts of war and leadership. Decades later, in 2015, he revealed another truth: during this period, he had secretly worked as an unpaid MI6 informant. Journalism, espionage, danger—his life was already a thriller.

From Broke to Bestseller: Reinventing the Thriller

In 1970, back in England and broke, Forsyth decided to write a novel. Not out of ambition—but survival. He approached it like journalism: research first, writing second. For six months, he reconstructed a hypothetical plot to assassinate President de Gaulle.

The result?

The Day of the Jackal (1971)—a revolutionary thriller.

Publishers rejected it at first. Then it exploded.

Six million copies sold. Edgar Award for Best Novel (1972). A major film adaptation. Intelligence agencies reportedly studied its realism. Forsyth had found the formula: real events + forensic research + relentless suspense. He didn’t write fiction. He engineered it.

The Odessa File: Nazi Secrets and Real-World Consequences

Forsyth’s second act came fast. The Odessa File (1972) turned the spotlight on unpunished Nazis. Inspired by a newspaper article, he followed journalist Peter Miller as he uncovers ODESSA, a clandestine network protecting SS officers.

Forsyth’s research was legendary—speaking to Nazi hunters like Simon Wiesenthal, interviewing survivors, tracking financial trails. He named real war criminals, including Eduard Roschmann, the “Butcher of Riga.”

The novel sold millions and became a 1974 film. Astonishingly, screenings in Argentina led to Roschmann’s identification and arrest. Forsyth’s fiction caused real-world justice.

Critics hailed his precision. Readers were electrified. Debate sparked: Was ODESSA real? Historians saw fragments, but Forsyth gave it mythic power.

By then, he had a three-book deal, millions of readers, and a new title: The Master of the Modern Thriller.

Legacy: The Outsider Who Never Stopped Watching

Forsyth kept writing:

- The Dogs of War (1974) – African coups and mercenaries

- The Fourth Protocol (1984) – Soviet nukes and spies

- The Fist of God (1994) – Gulf War intelligence

- And more…

Thirteen novels, non-fiction works, short stories, memoirs.

In 2015, he published The Outsider: My Life in Intrigue, where he finally told the whole truth—about MI6, assassins, dictators, and the razor’s edge between journalist and spy.

He remained fiercely independent in politics:

- Criticised Tony Blair over Iraq

- Supported Brexit

- Exposed hypocrisy on all sides

Honors followed:

CBE (1997) and the Crime Writers’ Association Diamond Dagger (2012).

On June 9, 2025, at 86, Frederick Forsyth passed away in Buckinghamshire. But even in death, he wasn’t done.

A Final Twist: The Hunter Returns

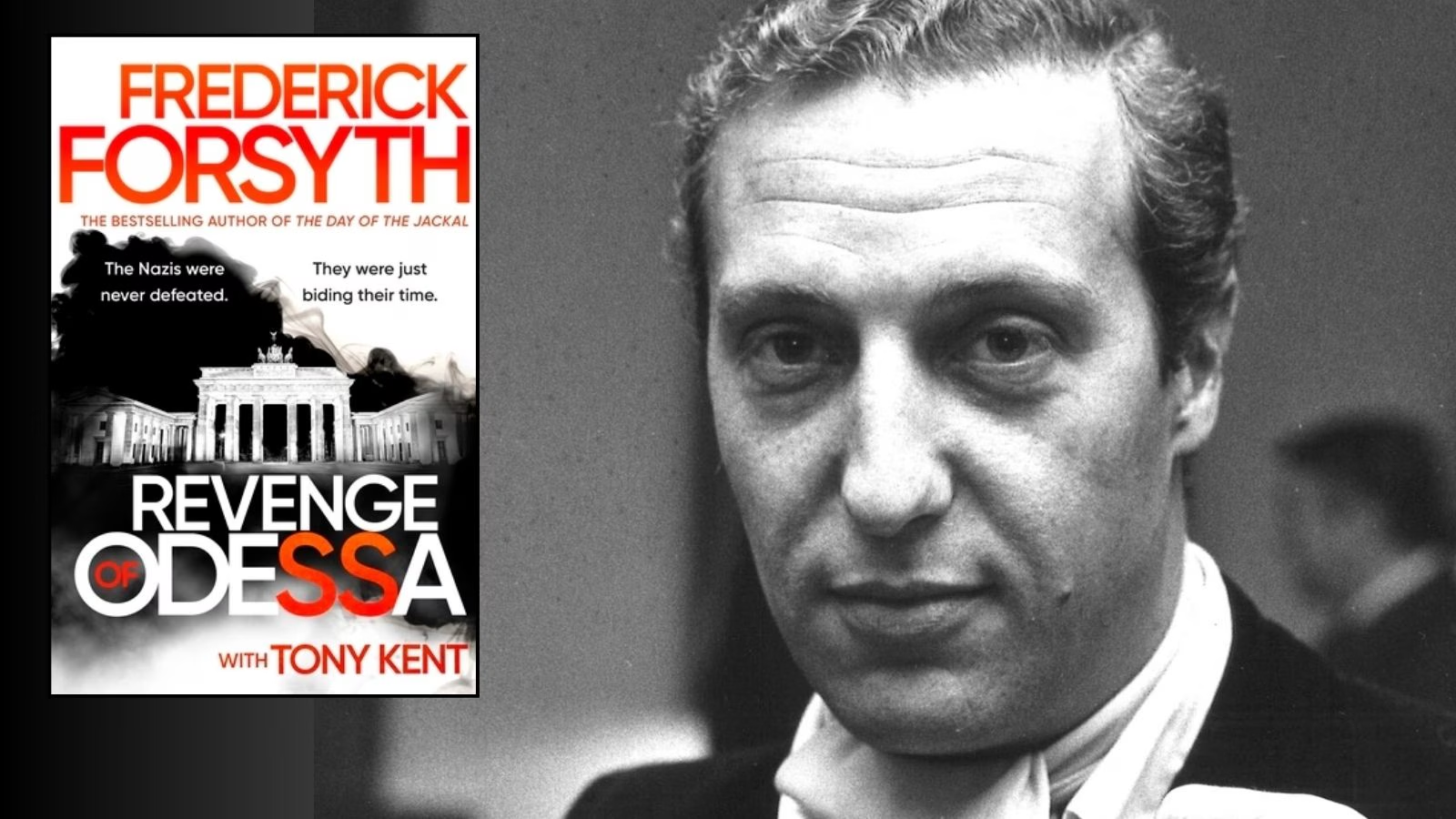

Months after his passing, Penguin Random House announced Revenge of Odessa (November 2025)—a sequel co-written with Tony Kent before his death. Peter Miller returns, hunting a new breed of neo-Nazi threat in the digital age.

It is a perfect circle.

Forsyth’s first moral crusade—tracking Nazi evil—rises again in the 21st century. His voice lives on, warning us once more:

The past never stays buried.

The Eternal Outsider

Forsyth once wrote: “A journalist must remain detached, like a bird… probing, commenting, but never joining.”

He lived that mantra—observing, questioning, exposing.

He flew with fighter pilots, ate with soldiers, argued with presidents, spied for MI6, and wrote stories that made the world tremble.

He wasn’t just a writer.

He was evidence that truth, when told with courage, can be more thrilling than any fiction.

Frederick Forsyth didn’t just write the modern thriller.

He lived it.