Manoj Singh, Retd IAS, ex ACS, UP Govt

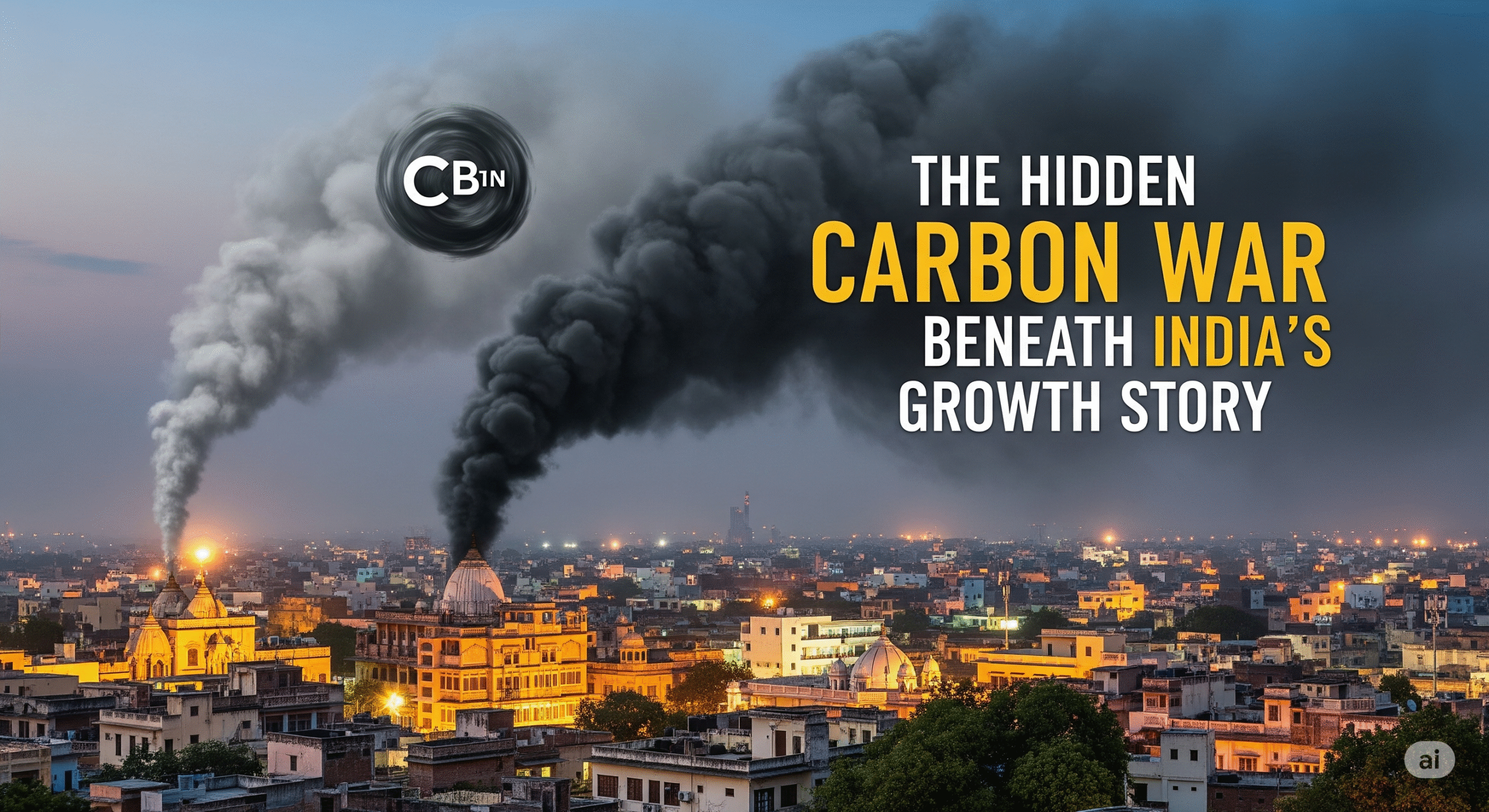

New Delhi: For over a century, India’s economic transformation has surged forward on the shoulders of coal-fired power, oil-fueled industry, and steel-driven infrastructure. But beneath this ascent lies an invisible war—one waged silently by forests, rivers, coasts, and soils that have absorbed a remarkable portion of the damage. A new analysis shows that since 1920, India’s natural ecosystems have sequestered between 60 to 80 percent of the country’s historical carbon dioxide emissions. Yet despite their resilience, India remains a net carbon emitter, a stark reminder that nature alone cannot undo the sweeping impact of industrialization.

From the colonial era to the post-independence boom and the modern liberalized economy, India has released between 48 to 56 billion tons of CO₂ into the atmosphere. During the British Raj, the development of railroads and early industries generated about 3 to 4 gigatons of emissions. Post-1950, as newly independent India invested in steel plants, dams, and refineries, emissions climbed to 10 to 12 gigatons. The real explosion came after 1990, with rapid urbanization, an expanding transport sector, and a rise in fossil fuel consumption, adding another 35 to 40 gigatons to the tally. This relentless growth in emissions has far outpaced the country’s capacity to store carbon through natural means.

Yet throughout this carbon-heavy century, India’s ecosystems fought valiantly. The Himalayas played a crucial role through the weathering activity of the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, which together helped trap an estimated 5 to 8 gigatons of carbon in sediments. These sediments were ultimately buried deep into the Bengal Fan, a vast underwater basin that has sequestered between 10 to 20 additional gigatons of carbon over millennia. Forests too contributed substantially, with remaining woodlands absorbing 15 to 20 gigatons despite waves of deforestation. Traditional farming practices that enriched the soil with organic matter helped store 2 to 4 gigatons of carbon, though much of this has been eroded by the spread of chemical agriculture.

Coastal mangroves—particularly in the Sundarbans—also played a vital role. Though small in area, they absorbed between 2 to 4 gigatons of carbon. However, nearly 40 percent of India’s mangroves have disappeared since the 1940s, sacrificed to urban development, aquaculture, and infrastructure. Despite all this effort by nature, the balance began to tip after 1990, when emissions began to triple. As fossil fuel use intensified, deforestation and wetland destruction crippled natural carbon sinks. Today, India emits about 3.4 gigatons of CO₂ annually, while its ecosystems can sequester only 1 to 1.5 gigatons in return.

Environmental economists caution that India is not just exhausting present-day resources—it is burning through carbon storage that took millions of years to build. The sedimentary vaults beneath the Bay of Bengal, once nature’s long-term climate insurance, are no match for the country’s accelerating carbon output. The data paints a sobering picture: while the Himalayas, mangroves, and traditional agro-ecological systems have acted as robust carbon capturers, they are no longer enough to balance the country’s emissions.

What’s clear is that India’s carbon narrative is one of both resilience and recklessness. The same land that once buffered the impact of climate change is now fraying at the edges. Forest cover has declined from 40 percent in 1900 to just 24 percent today. Coastal ecosystems, which once formed protective blue carbon zones, have been decimated. Wetlands have been drained, and industrial agriculture has depleted the soil’s natural carbon-holding capacity.

To chart a sustainable future, India must look to both restoration and innovation. A commitment to restoring 26 million hectares of degraded forests under the Bonn Challenge is a critical first step. Preserving and rehabilitating mangroves and seagrass beds can rebuild blue carbon reservoirs. In the heartland, rewarding farmers who use carbon-storing techniques—like no-till agriculture, biochar, and organic composting—can begin reversing the damage done by decades of chemical dependence. Most importantly, none of this will matter unless India tackles the elephant in the room: fossil fuels. Trees, rivers, and soils cannot compensate for the 3.4 gigatons of carbon released every year. The clean energy transition is not just desirable—it is necessary for survival.

India’s unique geography and rich biodiversity once gave it an edge in the global climate fight. But as economic growth has bulldozed through ecological boundaries, the nation now stands at a crossroads. The coming decades must be marked by a renewed partnership with nature. Clean energy, green infrastructure, and aggressive conservation must form the backbone of India’s development model. The ecosystems that once saved us from disaster cannot continue this war alone.

The real story beneath India’s carbon emissions isn’t just one of environmental degradation—it is one of nature’s heroic resistance. From the Himalayan peaks to the mangrove-lined deltas, India’s landscapes have held the line longer than most. But they cannot be the only defense. If we are to win the carbon war, it’s time to stop treating nature as an afterthought and start treating it as a partner. As one scientist put it, “The Himalayas and mangroves saved us from catastrophe. Now, it’s our turn to save them.”