Lucknow: Lucknow, the famed “City of Nawabs,” is more than just a cultural gem of northern India—it is a crucible where history, politics, and art have collided for over two and a half centuries. From the grandeur of the Nawabi courts and their syncretic culture to the revolutionary fires of 1857, from the stirring intellectual movements of the early 20th century to the bustling modern capital of Uttar Pradesh today, Lucknow’s story is one of resilience, grace, and transformation.

Lucknow: Lucknow, the famed “City of Nawabs,” is more than just a cultural gem of northern India—it is a crucible where history, politics, and art have collided for over two and a half centuries. From the grandeur of the Nawabi courts and their syncretic culture to the revolutionary fires of 1857, from the stirring intellectual movements of the early 20th century to the bustling modern capital of Uttar Pradesh today, Lucknow’s story is one of resilience, grace, and transformation.

This account traces the city’s defining chapters since 1775, when Lucknow was declared the capital of Awadh, with a special emphasis on its contributions to India’s freedom struggle.

The Nawabi Era: Foundations of Splendor (1775–1856)

Lucknow’s tryst with history took a decisive turn in 1775, when Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula shifted the capital of Awadh from Faizabad to Lucknow. This decision ushered in a golden age of culture, politics, and architecture that continues to define the city’s identity.

The Nawabs, descendants of Mughal governors, cultivated what came to be known as Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb, a syncretic ethos that harmonized Hindu and Muslim traditions. This spirit permeated everything—from festivals and literature to cuisine and architecture.

Architecturally, the Nawabi period remains Lucknow’s proudest inheritance. The Bara Imambara, commissioned by Asaf-ud-Daula in 1784 as a famine relief project, not only provided sustenance for thousands of workers but also created one of the world’s largest arched halls without pillars. Its adjoining Bhulbhulaiya (labyrinth) continues to fascinate visitors with its mysterious passageways. The Rumi Darwaza, a 60-foot ornate gateway modeled after Istanbul’s gates, became Lucknow’s emblem of grandeur, while the Chota Imambara, built in 1838, dazzled with chandeliers and intricate stucco work.

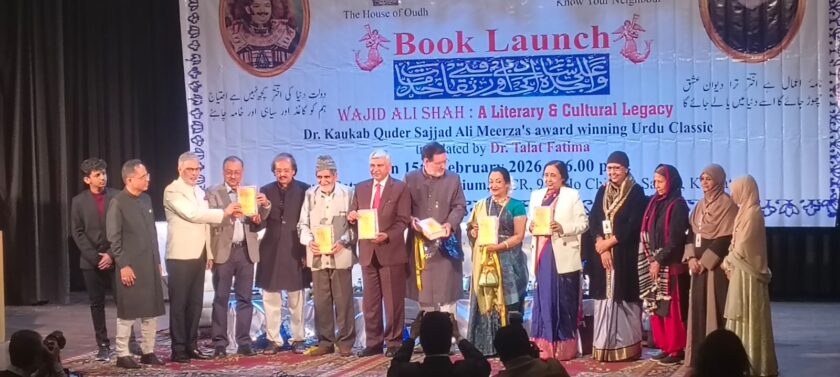

But it was not just monuments that flourished. The Nawabs’ patronage nurtured Urdu poetry, Kathak dance, and Hindustani classical music. The last Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah, though deposed by the British, was himself a poet, playwright, and dancer, who left an enduring artistic legacy. Ministers like Raja Tikait Rai promoted interfaith harmony, sponsoring temples alongside mosques, underscoring Lucknow’s composite culture.

The culinary revolution of the period gave India the delicate flavors of Awadhi cuisine—dum pukht biryani, galouti kebabs, kormas, and sheermaal. Dining became performance, served with tehzeeb (etiquette), a refinement that turned everyday meals into poetry.

This era laid not only the architectural and cultural identity of Lucknow but also the seeds of its political defiance, which would erupt with revolutionary fury in 1857.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857: Lucknow’s Defiant Stand

The year 1857 marked Lucknow as one of the fiercest battlegrounds of India’s first war of independence. The annexation of Awadh by the British in 1856, the dethronement of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, and widespread discontent among sepoys over greased cartridges ignited rebellion.

The Siege of Lucknow, beginning on May 30, 1857, became one of the rebellion’s defining episodes. Indian soldiers, civilians, and leaders rose in unison, surrounding the British Residency, where colonial officials and their families were barricaded. The siege stretched until November, involving waves of desperate fighting.

The conflict was brutal. The Sikandar Bagh massacre on November 16, 1857, saw over 2,000 Indian rebels killed by British forces—a moment immortalized in Felice Beato’s famous photograph. Yet the spirit of defiance endured, led by extraordinary figures.

Among them, Begum Hazrat Mahal, wife of Wajid Ali Shah, emerged as a towering leader. From the Kaiserbagh Palace, she organized troops, administered the city, and became a symbol of resistance. Another unsung hero was Uda Devi, a Dalit woman warrior who, legend says, fought valiantly from atop a tree at Sikandar Bagh, taking down British soldiers before falling herself.

Though the rebellion was eventually suppressed, Lucknow’s scars became emblems of resistance. The ruins of the Residency stand today not merely as relics but as living testimony to Lucknow’s defiance—a memory that would fuel later freedom struggles.

Between Revolt and Reform: Lucknow as a Political and Intellectual Hub (1857–1947)

In the aftermath of the revolt, the British annexed Awadh and shifted the provincial capital to Allahabad, wary of Lucknow’s rebellious zeal. But Lucknow did not recede into silence. Instead, it transformed into an intellectual and political hub, scripting some of the most important chapters of India’s nationalist movement.

The Lucknow Pact of 1916 remains a milestone. Hosted at the Baradari of Wajid Ali Shah, it brought together the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League. Leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Muhammad Ali Jinnah signed an agreement demanding greater self-governance. The pact, rooted in Hindu-Muslim unity, underscored Lucknow’s reputation as a crucible of political negotiation.

Education became another front of resistance. The founding of the University of Lucknow in 1920 created a vibrant intellectual space. Students participated actively in protests, debates, and boycotts during the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–22). Markets like Chowk and Aminabad transformed into arenas of swadeshi, rejecting British goods and embracing indigenous industries.

Revolutionary fervor also found its stage in Lucknow. The Kakori Conspiracy of 1925, orchestrated by the Hindustan Republican Association, shook the colonial administration. Revolutionaries including Ram Prasad Bismil, Ashfaqullah Khan, Rajendra Lahiri, and Roshan Singh robbed a train carrying government funds near Lucknow to fuel their movement. Arrested and tried in Lucknow, their sacrifice inspired generations. The Kakori Shaheed Smarak, erected decades later, stands as a reminder of their courage.

Lucknow’s contributions continued through the Civil Disobedience Movement (1930–34), when residents organized salt marches, boycotted cloth shops, and staged protests. Women, echoing Begum Hazrat Mahal’s legacy, played critical roles, leading rallies and confronting police crackdowns. During the Quit India Movement of 1942, Lucknow once again buzzed with underground activity. Hazratganj and Kaiserbagh became nerve centers of clandestine meetings, while students carried messages and pamphlets across the city.

Colonial Transformations: Western Influence and Cultural Continuity

Even as political unrest surged, British colonialism reshaped Lucknow’s landscape. Institutions like La Martiniere College (1869) and Canning College introduced Western education, paradoxically fueling nationalist thought among youth. Colonial architecture left its imprint with the Husainabad Clock Tower and government offices, blending Victorian and Indo-Islamic styles.

Yet, despite colonial dominance, Lucknow preserved its cultural resilience. The Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb thrived in shared festivals like Holi and Muharram. Crafts such as Chikankari embroidery and Zardozi found admirers worldwide. In 1936, Lucknow hosted the First All-India Music Conference, reinforcing its position as a cultural hub amid political upheaval.

Post-Independence: A City Reinvented (1947–Present)

Independence brought new roles for Lucknow as the capital of Uttar Pradesh. The city faced challenges of partition-related migrations, communal tensions, and administrative restructuring, but its resilience carried it forward.

Lucknow evolved into a hub of education and governance. Institutions like King George’s Medical University, Indian Institute of Management Lucknow, and the Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University added to its academic and professional stature. Politically, Lucknow became an influential constituency, represented by stalwarts such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

The city’s cultural fabric occasionally frayed—episodes like the 1984 anti-Sikh riots remain dark chapters—but its composite spirit endured. In recent decades, Lucknow has embraced modernization with projects like the Lucknow Metro (2017) and expanding IT and business corridors, while preserving its historic monuments.

The post-1990s era also saw the rise of Dalit and Bahujan identity, with memorials dedicated to Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and social reformers transforming the cityscape. These reflect Lucknow’s evolving role as a stage for political assertion and cultural memory.

Cultural Continuity and the Modern Identity

Today, Lucknow seamlessly blends Nawabi charm with modern ambition. Its bustling Hazratganj market, Chowk lanes, and food streets celebrate Awadhi cuisine, while its heritage sites like the Residency, Bara Imambara, and Rumi Darwaza remain magnets for tourists and scholars alike.

The city’s literary traditions thrive through writers, historians, and journalists who continue to narrate its layered past. Festivals, craft bazaars, and the enduring popularity of Awadhi cuisine remind residents and visitors alike that Lucknow’s culture is as alive as its politics.

Most of all, Lucknow’s enduring role in India’s freedom struggle—from the **Siege of 1857 to the Kakori martyrs, the Lucknow Pact, and Gandhian movements—remains central to its identity. Monuments like the Residency Museum and Kakori Shaheed Smarak preserve these memories for posterity.

A City of Enduring Legacies

Over the past 250 years, Lucknow has scripted chapters of unmatched cultural grandeur, revolutionary defiance, and modern reinvention. Its story is one of syncretism and struggle, where poetry and politics, food and philosophy, coexist.

From the Nawabi courts that celebrated refinement, to the rebels of 1857 who laid down their lives, from the revolutionaries of Kakori to the unifying voices of the Lucknow Pact, the city has stood as a beacon of resilience and creativity.

Lucknow today embodies both heritage and progress—a city where dum biryani simmers beside gleaming metro trains, where monuments whisper stories of defiance, and where tehzeeb continues to define everyday life. It remains, in every sense, a city where history is not just remembered but lived.