Lucknow/Delhi: India’s agricultural sector covers nearly 55 per cent of the country’s land, contributes about 18.3 per cent to Gross Value Added (GVA), and remains the primary source of livelihood for over 42 per cent of the population. At the same time, India achieved 250 GW of renewable energy capacity in 2025 and has already met half of its 500 GW non-fossil fuel target for 2030, with solar power emerging as the backbone of clean energy growth.

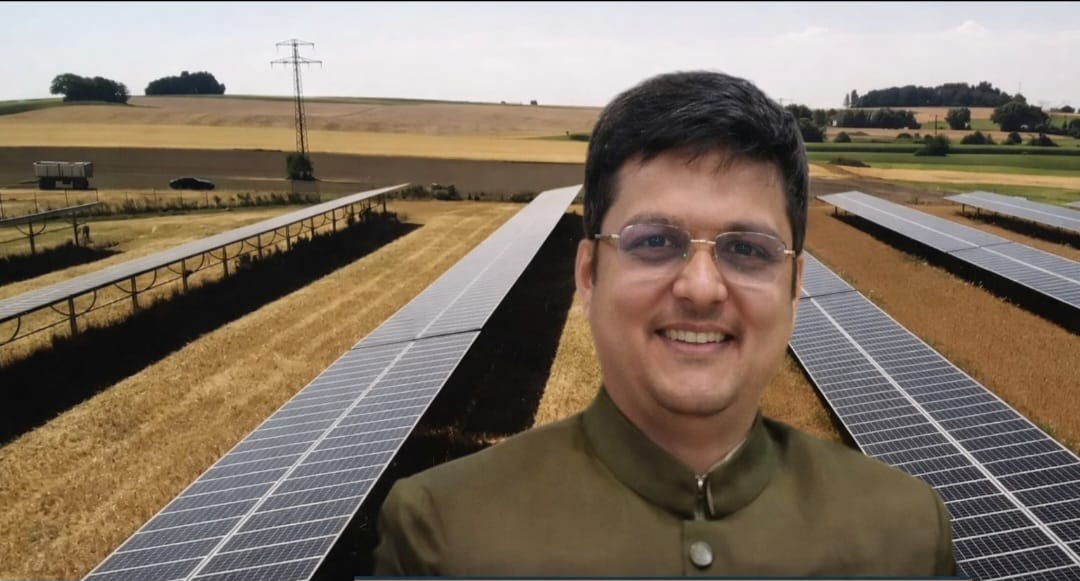

Against this backdrop, Pulkit Shrotri highlighted that agrivoltaics (Agri-PV)—often referred to as the country’s potential “third crop”—can play a transformative role by integrating food and energy security. Agri-PV allows agriculture and clean energy to complement each other, offering farmers new income streams while eliminating competition between farmland and renewable energy projects. However, despite its promise, several challenges continue to hinder its large-scale adoption in India.

Technical and Infrastructure Challenges

Agri-PV projects are typically utility-scale and are affected by limitations within DISCOMs and transmission systems. In many northern and central states, DISCOMs face surplus electricity during solar hours but shortages during evening peak demand. Excess renewable energy injected into the grid often remains underutilised due to inadequate feeder segregation and the absence of smart inverters. Until enabling policies are enforced, DISCOMs may also have to bear the cost of reactive power compensation.

Policy and Regulatory Barriers

A lack of a supportive policy ecosystem and weak inter-departmental coordination complicate project development. Existing land laws and tax regulations differentiate between agricultural and non-agricultural activities, creating hurdles for integrated Agri-PV models. Ambiguous definitions, uniform ceiling tariffs that ignore regional land cost variations, complex open-access rules, high cross-subsidy surcharges, and inadequate feed-in tariffs further reduce project viability.

Research, Crop, and Environmental Constraints

Limited budgets for research and development restrict innovation, while insufficient data on crop micro-environments and testing models hampers diversification. Current Agri-PV projects support only a narrow range of crops, often lacking strong value chains or price support mechanisms. Additionally, existing technologies struggle to align with local ecosystems, biodiversity, and soil conservation requirements.

Financial, Capacity, and Awareness Gaps

High upfront costs, limited access to low-interest finance, lack of guaranteed loan mechanisms, and inadequate policy backing make lenders cautious. At the grassroots level, low financial literacy, limited technical knowledge for operations and maintenance, weak grievance redressal systems, and poor awareness of suitable crops further slow adoption.

The Way Forward

Experts stress that unlocking the full potential of Agri-PV requires a robust policy framework, smart inverter deployment, feeder segregation, and a shift from subsidy-based support to ownership-driven models backed by interest subvention and attractive feed-in tariffs. Enhanced R&D, inter-departmental convergence, farmer training, and environmentally sensitive Agri-PV systems are also critical.

Shrotri noted that reforms at the government level could benefit both DISCOMs and farmers. Shifting highly subsidised rural domestic and agricultural loads to Agri-PV can significantly reduce daytime peak demand, ease DISCOMs’ financial burden, help manage evening peaks, and cut emissions. At the same time, farmers and developers can improve profitability by selling power locally and to the grid while strengthening crop diversification through well-established value chains.

Despite existing hurdles, Agri-PV remains a promising pathway for India to balance development, sustainability, and climate resilience—provided these challenges are addressed in a coordinated and timely manner.