New Delhi: In debates on military aviation acquisitions, attention often centres on induction timelines—the moment an aircraft formally enters service. However, defence experts note that induction is only the first step. The real measure of combat effectiveness lies in operational maturity, a phase that determines whether an aircraft can be deployed seamlessly, sustained over time, and fully integrated into combat doctrine.

Operational maturity typically takes years after induction, encompassing pilot and ground crew proficiency, stable supply chains, weapons integration, software refinement, and tactical evolution. While induction marks formal acceptance, maturity defines real battlefield readiness.

For indigenous platforms such as India’s Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) TEJAS, this journey has been gradual. The TEJAS achieved Initial Operational Clearance (IOC) in 2013, Final Operational Clearance (FOC) in 2019, and squadron induction in 2016. Yet defence planners estimate that true operational maturity generally requires 8 to 12 years post-induction, as systems are refined through exercises, feedback loops, and real-world deployments.

Several factors extend this timeline for home-grown aircraft. Training syllabi evolve alongside software updates and new weapon integrations. Domestic supply chains, still maturing, often face delays in spares and components. Additionally, operational doctrines develop through joint exercises, revealing challenges in integrating new aircraft with legacy fleets such as the Su-30MKI and Mirage-2000.

In contrast, imported aircraft often reach maturity faster. The Dassault Rafale, inducted into the Indian Air Force in 2020, achieved near-full operational maturity within two to five years. Already proven in service with the French Air Force, the aircraft arrived with mature avionics, engines, and weapon systems. India’s focus was largely on infrastructure adaptation, simulator integration, and local maintenance facilities rather than fundamental development.

This disparity highlights a key procurement trade-off. Indigenous platforms build long-term self-reliance but demand patience, while imports deliver rapid capability by inheriting operational experience from abroad. Historical examples reinforce this pattern. The Su-30MKI, inducted in 2002, took nearly a decade to reach peak maturity due to production ramp-ups and integration challenges. Conversely, aircraft inducted with established foreign maturity have historically achieved readiness much faster.

Looking ahead, next-generation indigenous projects like the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) are expected to follow a similar extended maturity curve, potentially spanning a decade or more from first flight to full-spectrum operations. Meanwhile, follow-on orders for improved variants such as the TEJAS MK-1A aim to shorten this cycle by leveraging lessons learned and more stable supply chains.

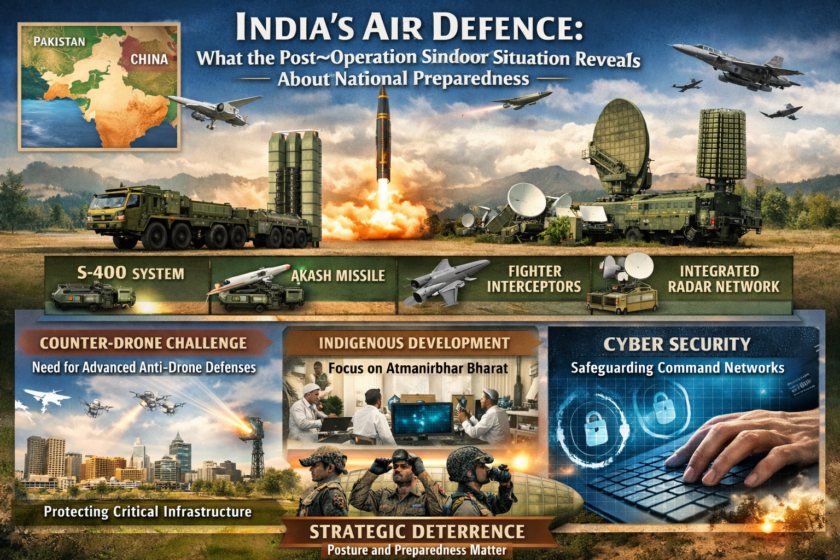

Strategically, India’s approach reflects a balance between urgency and autonomy. With ongoing security challenges on multiple fronts, platforms with shorter maturity timelines provide immediate deterrence, while indigenous programs secure long-term technological independence.

Ultimately, defence analysts argue that operational maturity—not induction—defines air power. While induction announcements generate headlines, it is sustained readiness, integration, and reliability that deliver real combat advantage. As India shapes future procurements, embedding maturity benchmarks alongside cost and performance will be crucial to maintaining a decisive edge in an increasingly contested airspace.