Lucknow: When Bollywood goes looking for grandeur and gravitas, for nostalgia draped in sherwanis and poetry, or for the earthy pulse of small-town India, it often returns to a familiar muse: Awadh. The region — anchored in Lucknow but stretching across Faizabad, Ayodhya, and their hinterlands — has long offered Hindi cinema a backdrop of refined culture, layered histories, and irresistible contradictions.

Lucknow: When Bollywood goes looking for grandeur and gravitas, for nostalgia draped in sherwanis and poetry, or for the earthy pulse of small-town India, it often returns to a familiar muse: Awadh. The region — anchored in Lucknow but stretching across Faizabad, Ayodhya, and their hinterlands — has long offered Hindi cinema a backdrop of refined culture, layered histories, and irresistible contradictions.

Awadh is not just a location. It is a mood, a character, a metaphor. It is the shimmer of a chikankari dupatta in a Mehboob song, the languid twirl of a courtesan’s ghungroo in Umrao Jaan, the political intrigue of Shatranj Ke Khiladi, and the youthful banter of Tanu Weds Manu. Over decades, filmmakers have turned to Awadh to dramatize romance and rebellion, nostalgia and modernity, poetry and politics. And Bollywood, in turn, has given Awadh an afterlife in celluloid that has outlived Nawabs, kingdoms, and empires.

Nawabi Roots and Ganga-Jamuni Glow

Awadh’s cinematic journey begins with its real-world history. From the grandeur of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s court to the syncretic Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb that blended Hindu and Muslim traditions, Awadh has always thrived on cultural confluence. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Lucknow’s havelis echoed with Urdu mushairas, Kathak performances, and qawwalis, while its streets filled with tantalising aromas of kebabs and biryanis.

It is this opulent yet inclusive culture that Bollywood first fell in love with. The palaces, the poetry, the courtesans, the chess players — all offered readymade drama. Filmmakers mined these legacies, turning Awadh’s real history into cinematic allegory for fading glory, colonial upheaval, and eternal romance.

Early Bollywood: A Land of Lost Grandeur

The romance began earnestly with Pakeezah (1972). Kamal Amrohi’s magnum opus was less a film than a visual ode to Lucknow’s tawaif culture. The courtesan Sahibjaan, played by Meena Kumari, became a tragic heroine, caught between love and stigma, while the bazaars and kothas of Awadh shimmered with melancholic beauty. Every ghazal in the film — from Chalte Chalte to Inhi Logon Ne — was steeped in Urdu lyricism that owed itself to Awadh’s cultural fountainhead.

Then came Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1977). Adapted from Premchand’s short story, it was a biting commentary on decadence at the twilight of Nawabi rule, when aristocrats played chess as the British annexed their kingdom. Ray’s painstaking recreation of 19th-century Lucknow, his nuanced portrayal of Wajid Ali Shah as poet rather than playboy, and his use of Awadhi Urdu made the film a cultural document as much as cinema.

These films etched an archetype: Awadh as the land of bygone refinement — a little tragic, a little decadent, always poetic.

Archetypes: The Tawaif and the Nawab

No region has gifted Bollywood such enduring tropes as Awadh has with the tawaif and the nawab.

The tawaif — equal parts temptress, poetess, and prisoner — became a fixture in Hindi cinema. Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan (1981), starring Rekha, remains the definitive portrait. Shot like a miniature painting, every song was a ghazal in motion: Dil cheez kya hai, In aankhon ki masti. The courtesan’s kotha became both cultural salon and gilded cage, echoing the paradox of Awadh itself — glorious yet fragile.

The nawab, meanwhile, was often painted as refined but indulgent — a man of tehzeeb but also tragic weakness. From Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960) to Mere Mehboob (1963), Bollywood’s nawabs sighed in shayari, fell in hopeless love, and served as metaphors for Awadh’s genteel decline. Even when the scripts did not name Lucknow, the cadence of Urdu and the etiquette of tehzeeb betrayed their Awadhi DNA.

Contemporary Awadh: From Period Cinema to Pop

But Awadh is no museum piece. In recent decades, it has leapt into contemporary Bollywood with new avatars.

Films like Tanu Weds Manu (2011, 2015) brought Lucknow into the heart of small-town romcoms. The city became a playground for quirky characters and messy modern love, its bazaars and colleges serving as vibrant backdrops. Similarly, Ishaqzaade (2012) and Daawat-e-Ishq (2014) used Lucknow’s architecture and food to give romance a regional zest.

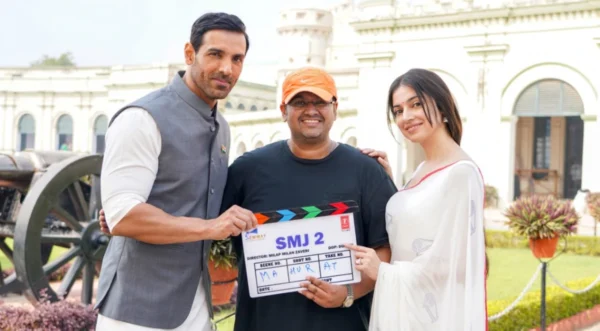

The city’s streets, from Hazratganj to Chowk, have become film sets, thanks to Uttar Pradesh’s film-friendly policies. Production houses find Lucknow’s mix of colonial relics, Nawabi havelis, and bustling markets irresistible. OTT platforms too have embraced the region: shows like Gullak and Panchayat may be set in nondescript UP towns, but their humour, language, and values echo Awadhi ethos.

Awadh today is both heritage and hipster — a place where biryani coexists with baristas, and Bollywood loves the contrast.

Food, Music, and Tehzeeb on Screen

Awadh’s cinematic presence is not just visual; it is sensory. The aromas of kebabs, galoutis, biryanis, and malai ki gilori waft through films like Daawat-e-Ishq, where food is both metaphor and mood. Awadhi cuisine, with its leisurely cooking and layering of flavours, mirrors Bollywood’s love for indulgent storytelling.

Music and dance are another gift. Kathak, patronised by Nawabs, has adorned everything from Devdas (2002) to Bajirao Mastani (2015). Urdu poetry, with its metaphors of longing, remains Bollywood’s romantic lingua franca — much of it seeded in Lucknow’s mushairas. Even contemporary tracks sneak in shayari, reminding us that Bollywood’s lyricism is indebted to Awadh.

Why Awadh Resonates

So why does Bollywood keep circling back to Awadh? The answers lie in three layers:

- History: Awadh offers ready-made drama — from Mughal patronage to colonial annexation. Its history is romance and tragedy rolled into one.

- Culture: The syncretic Ganga-Jamuni ethos provides Bollywood with a poetic antidote to modern polarisation. Awadh is shorthand for harmony.

- Practicality: Lucknow is affordable, film-friendly, and visually versatile. It looks like both a 19th-century court and a 21st-century small town.

- Above all, Awadh gives Bollywood something it craves: lyricism. Whether in courtesan couplets or college banter, the cadence of Awadhi speech makes for irresistible dialogue.

Going Beyond the cliche

Of course, there are risks. Bollywood sometimes flattens Awadh into clichés: the tragic tawaif, the decadent nawab, the endless mehfil. Modern voices want more. Films like Masaan (2015) — though set in Varanasi — hinted at new ways of telling North Indian stories without nostalgia traps.

The rise of OTT has accelerated this trend. Today’s audiences are as keen on stories of small-town start-ups or social change as they are on kothas and sherwanis. Awadh, with its blend of old-world charm and modern churn, is perfectly poised for this next phase.

Curtain Call: Lucknow as Bollywood’s Darling

In the end, Bollywood’s romance with Awadh is like a classic ghazal — sometimes wistful, sometimes playful, always melodic. From Umrao Jaan’s courtesan to Tanu Weds Manu’s small-town bride, from nawabs in silken robes to students in jeans, Awadh has shape-shifted across decades without losing its core identity of grace and tehzeeb.

If Mumbai is Bollywood’s factory, Awadh is its muse. It provides the tehzeeb to its romance, the tehraav to its poetry, and the tehniyat to its nostalgia. And as long as Hindi cinema seeks stories of longing and belonging, Awadh will remain its eternal darling — a reel kingdom of dreams built on real legacies.