New Delhi – The rich tradition of painting that flourished during the Pala dynasty of eastern India continues to resonate through time, influencing key Himalayan art forms such as Nepal’s Paubha and Tibet’s Thangka paintings. Although historical records about the continuation of this art form post-12th century are scarce, art historians agree that the spiritual and stylistic essence of Pala art found new life in these regions.

Emerging between the 8th and 12th centuries in the region of Magadha (modern-day Bihar and Bengal), the Pala school of art is most renowned for its intricate palm-leaf manuscript illustrations depicting Buddhist themes — including Bodhisattvas, mandalas, and sacred geometric forms. These delicate artworks, often created with mineral and vegetable dyes, were deeply meditative in nature, reflecting a synthesis of tantric and devotional iconography.

While the trail of Pala painting seems to fade in India after the 12th century, its spirit found a fertile ground further north. By the early 13th century, the visual language of Pala paintings had significantly shaped the development of Tibetan Thangka art and Nepalese Paubha paintings — traditions that continue to thrive in the Himalayan belt.

Though Thangka is a widely known term today, Paubha remains largely unfamiliar — even within India’s art discourse. However, art scholars and cultural custodians in Nepal assert its critical value and ancient lineage.

Influence on Tibetan Art

A comparative study of Pala sculpture and Tibetan bronze figures reveals striking similarities — particularly in the depiction of tantric deities such as Vajrayogini, Tara, and Avalokiteshvara. Tibetan Thangka paintings retain the linear grace and tranquil facial expressions that defined Pala icons. Sacred diagrams, meditation postures, and symbolic hand gestures (mudras) from Pala art also reappear with evolved interpretations in Thangka compositions.

Even the color palette and compositional frameworks echo their Indian origin, reinforcing the cross-cultural transmission of sacred art.

Rise of the Paubha Tradition in Nepal

In Nepal, it was the Newar community — a group of indigenous artisans and temple builders in the Kathmandu Valley — who preserved and transformed this sacred art into the Paubha tradition. Heavily inspired by Pala sensibilities, Paubha paintings focus on proportionate deities, ornate lines, and meditative postures.

Yet, the Newars added their own visual vocabulary — enriching the tradition with localized aesthetics and ritual significance. The term Paubha itself derives from the Sanskrit words patta (cloth) and bhattika (painting), referring to religious imagery painted on cloth.

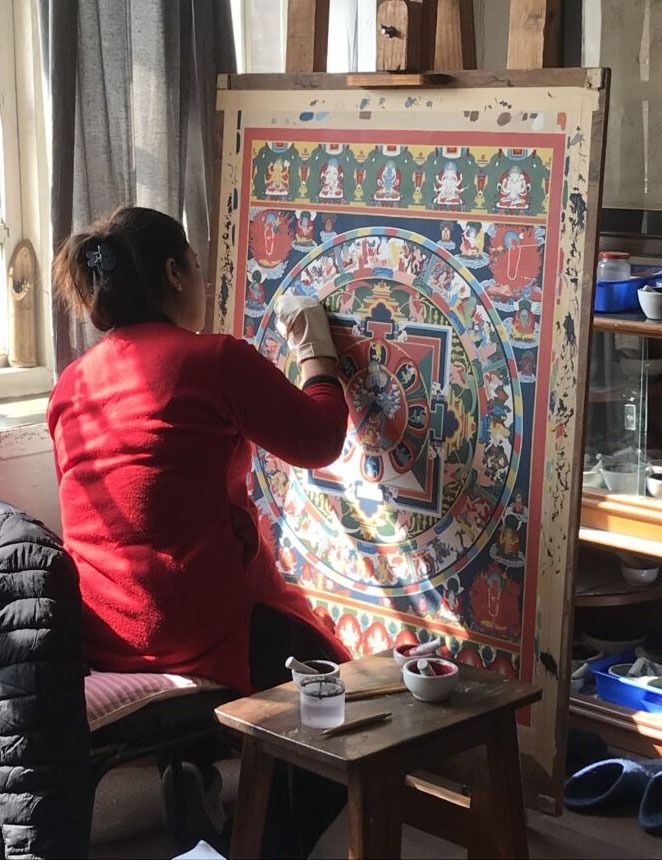

Unlike secular painting traditions, Paubha art is deeply ritualistic. Newar artists, often trained within family lineages and oral traditions, adhere strictly to iconographic guidelines rooted in ancient Sanskrit scriptures. Measurements, colors, and postures are determined not just by aesthetics but by sacred geometry and liturgical symbolism.

Importantly, the process of creating a Paubha is considered a form of worship. The final act of “opening the eyes” (Netra Daan) — where the deity’s eyes are painted last — is likened to Prana Pratishtha, the infusion of life into the divine form.

Bridging Art, Devotion, and Memory

Paubha painting is not merely visual art; it is a spiritual document. It records centuries of religious practice, cultural philosophy, and devotional sentiment — much like its predecessor, the Pala tradition. From Bodhisattvas and mandalas to narrative scenes of Buddhist and Hindu cosmologies, these artworks represent a living continuum of sacred aesthetics.

Today, while Pala manuscript illustrations survive only in museums and rare archives, their artistic DNA thrives in the living traditions of the Himalayas. Nepal’s Paubha artists continue to honor this legacy, painting not just images but entire worldviews — one brushstroke at a time.

As modern scholarship and cultural preservation efforts gain momentum, the Paubha and Thangka traditions are being rediscovered not just as Himalayan expressions, but as South Asian inheritances rooted in the philosophical and visual depths of ancient India.